Northern Argentina, freedom learning in Andes mountains

Argentina was a completely unplanned trip. One of those, when a friend tells you one evening: we have an empty spot! Do you want to join us? I did not hesitate for a moment, and the next day I was in Buenos Aires. This time I didn’t have to do anything: plan, worry, control everything. We were traveling with a guide who dealt with everything. I love preparing my travels. I use to stay up late at night reading guidebooks, websites, and search for photos from the target region. However, this kind of trip: when you get comfortably into the car and, as in my case, you have no idea where you are heading to, has its sweet charm of oblivion and adventure. You remember the images, and emotions evoked by them. Organizational details, logistics problems, and possible failures do not concern you.

It was my first trip outside Europe and I didn’t know what to expect. With a stimulated imagination and a totally open mind, being on the plane still, before the typical turbulences of the Atlantic coastal zone of South America, I took a quick look at the travel schedule. It was as follows: 3 days in Buenos Aires, 14-day drive by car through the Andes, return to the capital for one night, and departure back. Something dawned in my head, and I began to worry. Maybe I joined one of these specialized trips, where the whole group squeezes through narrow mountain caves, explores the area in search of geological gems, or climbs peaks four thousand meters above the sea? Turbulence, however, made me forget about doubts I had, and after a few days spent in Buenos Aires, we traveled north.

After landing by plane in the city of Salta, after a 2.5-hour flight from the capital, we switched to off-road cars. I thought then: it will be long, two weeks of my life, but with the kilometers traveled deep into the wild mountain region, I realized that what I would see is unique. For me, the beauty of the geological formations, in the Salta and Jujuy region of north-western Argentina, was an out of this world experience. In addition to the multitude of visual experiences and the exotic clash of cultures, one thing struck me the most – the unimaginable space – one that I had never experienced in Europe before. Accustomed to mountain landscapes, I admired uninhabited areas in many different countries, but those in Argentina were a completely different experience.

,,I remember this feeling when, looking at the horizon, surrounded only by the desert, I felt that some weight was falling off me. The burden of what I brought with me – attachment to something, duties towards someone, worries, and joy from time ago, was suddenly gone. I felt free. It was freedom without borders and witnesses. For the first time in my life, I felt a physical and mental lightness, and since then, I have been carrying it within me.”

My Andean discoveries:

1.Calchaquí Valleys, Valles Calchaquíes

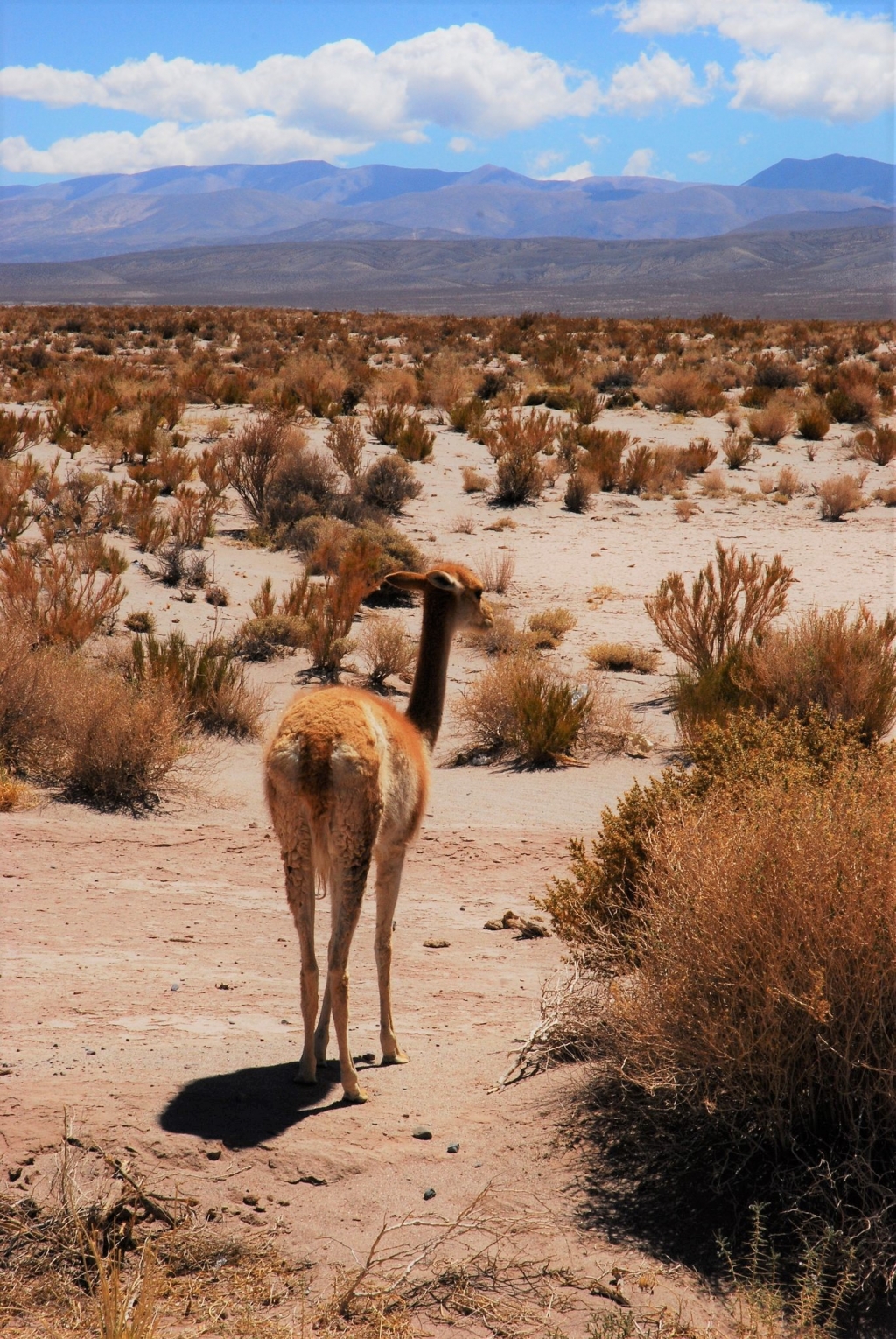

The Calchaquies valleys are a vast mountain area crisscrossed by numerous gorges in the provinces of Salta, Jujuy, Catamarca, and Tucumán. Geographically, they extend from the desert regions of the Altiplano in the north to the subtropical forests of their southern part. They are known for the contrasts of the environment and the richness of their geological forms. This is where the Quebrada de Las Conchas, Valle del Obispo, and Cordones National Park are located, which I will describe below. It is a scantily inhabited land. You can travel for days and not encounter a living soul along the way. On many sections of existing roads, the distances between the centers of civilization are significant. In case of a car breakdown, if you don’t have your own food resources, an additional gasoline canister, or a spare tire, means you are left on your own.

2.Salt Pan, Salinas Grandes

The salt pan is a white, flat space, once of a vast salt lake. Today, already without water, is a salt deposit used by the local desert population. Standing in the middle of this white spot, blinded by the glaring sun, I did not know if I was in the snow, in the desert, or somewhere on the hardened surface of some big sea. The novelty of the experience stimulated my imagination. Like an actor on the magnificent planet’s theater stage, standing with a complimentary glass of champagne, deceptively, and yet truly, I felt special.

3.The Bishop’s slope, La Cuesta del Obispo

Coming from Salta towards Cachi, we came across an extremely steep and twisted road section. Even today, off-road vehicles have some difficulty getting to the top of this mountain pass, covering 2,000 meters up. The road had existed since colonial times, when the trip between Salta and Cachi lasted two days, with a night stop just before the La Cuesta del Obispo. Nowadays, the journey takes about three hours. You can admire the magnificent asphalt road after reaching the top of the hill from the La Piedra del Molino viewpoint.

4.Cardones National Park

On the way from Salta to Cachi, just after La Cuesta del Obispo, you drive between thousands of cacti. It is the Los Cardones reserve, located on a large area of 64 hectares at 3,000 meters above sea level. The reserve includes mountain parts and flat valleys, crossed by an asphalt road called Recta del Tin Tin, thanks to which you can easily explore the park by car. The park’s name comes from the “cardón” cacti that grow aplenty on the plateau. They are its showcase. Ten meters high, they have served the local population for centuries, as a water reserve and a building material. Today, cacti stand as proud monuments guarding the inaccessible Andean mountains, hiding many secrets of the deserted wilderness.

6.The Mountain of Seven Colors, Cerro de Los Siete Colores, Purmamarca

Looking at the Hill of Seven Colors, this one time in my life, I regretted not becoming a geologist. I could then fully understand the complexity of this unique mountain range. I imagined that I would come back there someday, this time with a specialized group of experts, enjoying the phenomenon for longer. The mountain seems to be a colorful cloud that once fell from the sky. An expert eye will see here seven colors, arranged like in the rainbow: pink, white, brown, purple, red, green, and yellow. Each of them corresponds to a geological layer created in a different evolutionary age of the earth. The colors are visible outside of the mountain, due to the tectonic movements that occurred in the past. Locals say that the best time to watch the hill is 45 minutes after sunset when the colors saturate to the maximum, but I admired it at noon, and I cannot imagine anything more beautiful. Purmamarca – a town that lies at the foot of this fabulous hill, is equipped with a rich tourist offer as for the desert region. Here you will find cafeterias, shops with local products and guides available to tourists.

6.River Calchaquí, Río Calchaquí

The Calchaquí River begins with a narrow brook flowing from the sacred mountain of the Incas – Nevado de Acay. The stream further transforms into a river, changing its name many times along with its new tributaries. After 3,000 kilometers, at the end of its long journey, Calchaquí river proudly flows into the La Plata River, to connect with the ocean in the eternal water cycle of the planet.

Most rivers in northern Argentina have little water during the dry and cool summer season. In South America, the period from April to September is the calendar winter. The situation changes since October when temperatures rise, the snow in the Andes melts, and rainfall occurs. The narrow Calchaquí riverbed transforms into a vast, dangerous river. The natives use the fertile riverside and settle near for a definite period, grazing cattle and farming. In the flood period, they move to the mountains respecting the annual rhythm of nature.

7.Valley of Broken Arrows, Quebrada de Las Flechas

Like other large-area countries, Argentina also has its iconic road. Highway # 40 cuts all of Argentina from Bolivia in the north to Cabo Virgenes in the south, running along the Andes. In its Cafayate – Cachi section, we entered between the jagged rocks all of a sudden. Rock formations of Quebrada de Las Flechas grow straight from the underground. They incline, and some of them reach a height of 20 meters.

8.Amphitheater, El Anfiteatro, Quebrada De Las Conchas

Close to the city of Cafayate, there is a beautiful valley of Quebrada de las Conchas with red-brown rocks. The result of rapid tectonic transformations were chasms and hollows, and the biggest attraction here is the amphitheater rock – El Anfiteatro. It got its name because of the unique acoustics. Inside this round chasm, the human ear will catch even a whisper. In the ravine itself, you can often find natives playing instruments on the desert, that bring out the acoustic potential of this exquisite mountain hole.

9.Llullaillaco Mummies, Salta Archaeological Museum

To see mummified Inca children from 500 years ago, was a shocking experience for me. Two things contributed to this reaction; fantastically preserved bodies of three children, and the circumstances of their offering.

Inca cemeteries on the Llullaillaco volcano had been known since the mid-20th century. Many daredevils conquered the top of the volcano and reported the findings. In 1999, a trip organized by the National Geographic to search the mountain revealed the mummified corpses of three children. El Niño (boy), La Niña Del Rayo (girl of lighting), and La Doncella are unrelated children of families from the Inca elite, chosen as a sacrifice during the Capac Cocha ritual.

Capac Cocha ritual

This annual festival took place in the capital of the Inca empire, for the god Viracocha. Villages from all over the kingdom, sent one child with an escort to the city of Cuzco, to attend the festivities. After the ceremonies, the representation of the village returned home, and the chosen one was offered on the holy mountain, near his place of residence. Death came without pain. Coca or chicha leaves were given to the child, and when it fell asleep, it was taken to a snowy mountain peak and died by freezing.

Carefully selected for the ritual from their birth, El Niño, La Niña Del Rayo and la Doncella, dormant and buried in graves at an altitude of 6,739 m above the sea level, look like they don’t know about their sad destiny. Today they are exposed to the public view at the Archaeological Museum in Salta, and raise a strong controversy of the tribes to which mummified children belong ethnically. In every belief, the body of a deceased person is sacred and belongs to the Earth. There are many mummified corpses in the world exhibited in a museum. However, those in Salta are unique. Their excellent preservation, due to the specific conditions at the top of the Llullaillaco volcano, causes that, when looking at their dormant faces, the impression is as if the children were alive. Polemics also revolve around methods of their conservation. The capsules inside of which the mummies are located, thanks to sophisticated engineering, maintain similar conditions to those prevailing on the volcano. Despite this, the bodies of children in the last ten years deteriorated faster than for 500 years of resting in the Inca graves away from the civilization.

10.Andean villages

While in Buenos Aires, I had the impression that it did not differ much, from the big cities in southern Europe. The climate, colors and street lifestyle full of dynamism reminded me of Spain. Architecture evoked Madrid, and people with European features and light, and brown skin tones had the same habit of hanging out at the local cafeteria for hours, the way of saying hello, topics of conversation, and clothing.

In Salta on the other hand, to my amazement, more exotic faces and costumes unknown to me appeared. The more we delved into the desert areas of the Calchaquí valleys, the more we encountered Indian people. They were characterized by dark skin, jet-black hair, slanted eyes, a round, stocky figure, and faces full of wrinkles, reflecting the difficult living conditions and a hard spirit. The children here looked the same as the mummified ones, found in Llullaillaco, who lived 500 years ago. At first glance, some places looked as if time had stopped somewhere in the distant past. Life here seemed to be following eternal orders when people born and die according to nature to the rhythm of the changing seasons.

Walking, many times all alone in tiny Andean towns, I was often unpleasantly scrutinized by the eyes of exotic locals. Their faces reflected anger and resentment. I felt safe, yet unwanted.

The Calchaqui valleys have been inhabited for centuries by the Diaguita Indians. Descendants of this ancient, pre-Columbian culture are involved in farming, pastoralism, and pottery for generations. Their beliefs are associated with the cult of Mother Earth, and they once spoke kakán language – no longer used today. The Calchaquí tribe, today extinct, gave the name to the Calchaquí Valleys. In the 15th century, as a result of the expansion of the Inca state, the Diaguita were incorporated into its political borders. During the Spanish Conquest of South America, they were one of the communities defending their lands for the longest time. Over ten years of calchaquí wars, ended in brutal tribal division and deportation by Spanish troops, to destroy the uncomfortable opponent. The conquest and slavery of labor towards the natives lasted in Argentina until the 18th century. Argentina, after gaining its independence as a state, applied a policy of “invisibility” towards indigenous ethnic minorities. Only recently, adapting to world standards tackles the topic of equality for their Indian tribes. Understanding the turbulent history of these legitimate inhabitants of Argentina comes to my mind a similar phenomenon of Indians in North America. The incompetently hidden anger and dislike towards me – a white tourist from Europe, aroused a deep understanding of the people who resembled suffering of my polish compatriots, under the hard hand of the invaders, in difficult times of change.